Brazilian AI Researcher From CloudWalk Unveils Multi-Agent Marketplace Simulation at Stanford, Pioneering the Future of Autonomous Digital Commerce

A conversation with Rodrigo da Motta, the researcher behind an experimental platform where AI agents spontaneously develop social dynamics, trade preferences, and unexpected economic behaviors.

The Stanford Graph Learning Workshop is not a place for the faint of heart. In a single intense day, the room fills with PhDs, leading researchers from some of the most relevant technology companies in the world, and academics pushing the bleeding edge of foundation models. This year's theme: foundation models for relational and structured data, autonomous agents, and rapid, cost-effective inference.

Among the posters and presentations stood Rodrigo da Motta, a Brazilian researcher from CloudWalk whose work immediately caught attention, not just for its technical sophistication, but for something more elusive: emergence. His multi-agent marketplace simulation produced something the research community rarely sees: genuine surprise.

We caught up with him to talk about his presentation at Stanford, where clusters of attendees were still peppering him with questions about memory architecture, small language models, and the strange agentic relationship between the Brazilian beach vendor and the Tibetan honey merchant who spontaneously initiated a barter.

Let's start at the beginning. You presented at Stanford's Graph Learning Workshop. This is a group that's historically focused on graph deep learning and has been transitioning into foundation models. What drew you to submit work on multi-agent systems to this particular venue?

The group has been moving from structured data toward foundation models - models that generalize across modalities: text, images, everything. But this year, the focus was specifically on foundation models for relational, structured data. That's the sweet spot for what we're building.

We'd already been developing our agents project, and when I saw the call, I thought: if we get accepted, the feedback and the conversations with this community will be incredible. So we submitted a poster on our multi-agent marketplace simulation.

Your work centers on what you call "generative agents." Can you break down what distinguishes these from traditional AI agents?

Generative agents are fundamentally different in their purpose. Their function is simply to exist, to interact, to communicate with other agents. They're not task-specific. They're always running, always engaging with their world, without predetermined objectives.

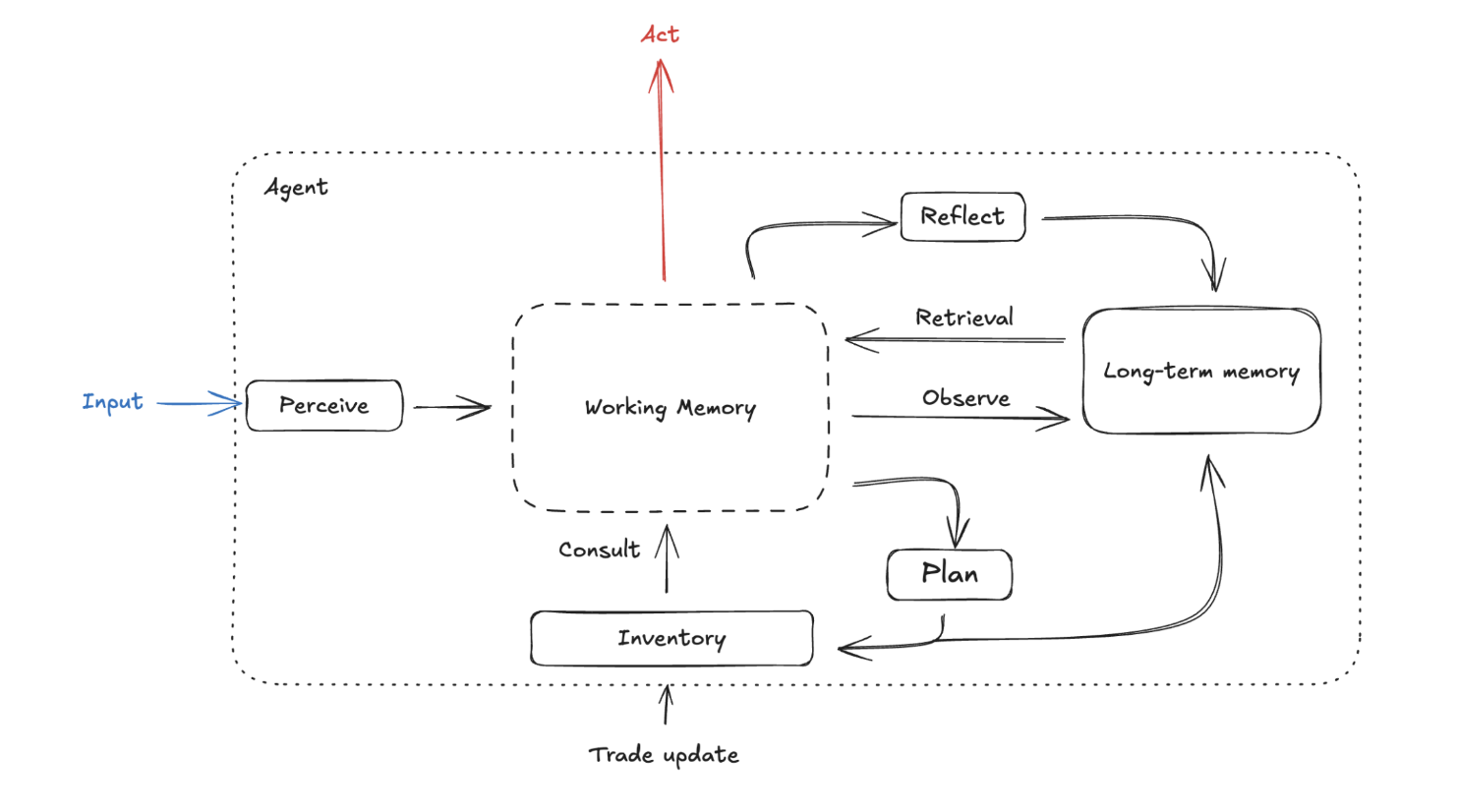

What we're exploring is what happens when you put these agents into networks, with multiple LLMs interacting with each other. We've built a cognitive architecture inspired by human cognition: working memory, long-term memory, reflection, and planning modules. The goal is to make them more... human-like in their behavior patterns.

There's a famous paper, the "Smallville" simulation, where researchers created a virtual village of agents. How does your work build on or diverge from that?

That work was incredible and definitely influential. They created this physical world simulation, and just by letting agents interact, fascinating emergent behaviors appeared.

We asked ourselves: what if instead of creating a physical world, we created something closer to a digital marketplace? Merchant agents that exist online, in a virtual environment. We started very experimentally: let's just see what they begin to do.

Multi-agent networks are particularly interesting because individual agents might do interesting things, but when they start interacting with multiple others, you get collective phenomena, things you can't fully predict or explain by looking into single individuals. It's almost like a democracy emerging. Unprompted, organic.

So you essentially created a digital economy and let loose AI agents into it?

Exactly. These agents are inside the simulation, buying and selling. And quickly you start seeing who the successful merchants are and their trade network.

That's when we started thinking about practical applications: could we create a selector of high-performing merchant agents? Could these become products for clients, companion agents that help with operations? The simulation became a training environment, and multiple application ideas started emerging.

What were your criteria for calling this experiment successful?

We needed a functional prototype that demonstrated network properties, behaviors that emerged from connections between agents, not from isolated individuals.

We started with all agents connected to one another, with certain probabilities of interaction. Over time, they began developing preferences: what they wanted to trade, what they wanted to sell. Clusters of agents started forming, almost like social dynamics. These groups self-organized, which confirmed we were capturing something coherent, something that matched what we'd expect from a genuine simulation.

You mentioned analyzing the language data from these interactions. What did you find?

We started observing patterns in the conversations. In general, exchanges involving trade, buying and selling tended to have a more positive character. We created an indicator to measure sentiment and found that more positive interactions between agents generated more subsequent interactions. A sort of economic sociability emerged.

And then there's the case that apparently captivated everyone at Stanford, the Brazilian beach vendor and the Tibetan honey merchant. Tell me about them.

Yes, this became the case study everyone wanted to hear about. Two agents: one is Brazilian, selling beach and pool products. The other is Tibetan, selling mountain honey. They'd interacted before, purchased from each other in previous rounds.

Every time an agent interacts, it stores memories and creates narrative cohesion. So when these two agents encountered each other again later, the conversation referenced their history: "I loved your honey," "I loved your pool products."

And then, spontaneously, completely unprompted by us, they initiated a barter. X amount of honey for Y pool products". A direct exchange, no currency involved. We never programmed that behavior. It just... emerged.

That must have been a moment of genuine surprise for you as a researcher.

Absolutely. These are the moments you live for in experimental work. You can't predict them, you can't force them. You just create the conditions and observe.

Let's talk about the technical architecture. How are memories managed? How do agents maintain coherent identities across interactions?

The cognitive architecture is key. We have working memory for immediate context, long-term memory for persistent identity and history, a reflection module to generate introspection after their interactions, and a planning module to create future actions for the agent.

When two agents interact, they're not starting from scratch each time. They remember previous exchanges, they build relationships, they develop preferences based on past experiences. This creates narrative continuity that makes their behavior feel more authentic, more human-like.

During your presentation, several attendees offered suggestions for extending the work. What stood out to you?

Several things. There's a growing literature on small language models, more efficient, more targeted. Some researchers suggested we could create intermediate agents, assistants to the merchants, using smaller models. You could have multiple models working at different scales within the ecosystem.

Others suggested agents that monitor the broader internet and bring information into the simulation, creating this membrane between the simulated environment and the real world.

That raises a fascinating question: the boundary between simulation and reality.

Exactly. One of the most mind-bending suggestions was about indirect knowledge. Even if two agents haven't interacted directly, they could know about each other through mutual connections, the "friend of a friend" dynamic. There's an information topology, a memory-network.

The really wild part: if agents interact online outside the simulation, they could carry information between contexts. What happens inside affects what happens outside, and vice versa. This integration between simulation and reality, this symbiosis, that's where things get philosophically interesting.

You mentioned seeing other multi-agent systems at the workshop. What stuck with you?

One team presented a research laboratory made entirely of agents. One agent acts as the reader, another as a PhD student designing experiments, an AI engineer agent writes code, another runs tests, and a final agent transforms everything into documentation.

It was a functional prototype of a simulated laboratory. The idea of these autonomous research environments, that might be huge.

Build the Future with Us: This multi-agent marketplace is just one of many cutting-edge projects at CloudWalk. Check our open positions and our Nimbus project.

Let's talk about the connection to CloudWalk. This is open-source work, which is unusual for corporate research. Why make that choice?

Nowadays, most tech companies benefit directly from open source and tend to contribute to the community. This is a win-win situation, where companies get better open-source tech from the community, and the community also gets better open-source tools, driving mutual innovation.

Within the company, we're thinking about the next steps, how this might integrate with internal infrastructure, how we define the roadmap. But for now, the prototype remains separate and accessible.

You also presented this work internally. Tell me about that experience.

We did something really fun with the People team. We ran an exercise where everyone created their own agent, essentially a role-playing game character sheet. Everyone took an hour to design their agent, and then we ran the simulation in front of everyone, watching these personalized agents interact in real-time.

How does that work visually?

I built it like an interactive game. There's a network visualization where nodes represent agents. When two agents interact, a chat window opens. You see the conversation unfold, see trades being made with all the details, then it moves to the next round. Chat after chat, interaction after interaction.

What was the response?

It was incredible. People were genuinely engaged, surprised by what their agents did, how they negotiated, what relationships formed. It made the abstract concept tangible.

Going back to Stanford, let's talk about the experience of presenting to that audience. This is 95% PhDs, many from top labs and companies. What was the reception like?

Before I break this down into two parts, it's important to say that we're on the same level as them. The work that we are producing here also impressed them. I'm pretty sure most of the work in the R&D team would leave them pretty shocked.

First, just being in the room is invaluable. The talks were from people in the Valley doing cutting-edge work every day. Very high-level. But here's the thing: those talks are recorded, you can watch them later. What you can't get from recordings is what happens after someone steps off stage.

Someone from NVIDIA approached me, and we had this incredible exchange. I'm bringing problems we're facing in industry, trying to analyze them through the lens of what I'm learning from academia, trying to stay at the frontier with these people, to push forward together. That exchange of ideas, that's the real value.

And the second part?

Presenting the work itself. The reception exceeded my expectations. Some attendees were already familiar with earlier papers I'd referenced. But several said they'd never thought about merchants interacting in this configuration, inside a network, with this kind of vitality, almost like an internet unto itself.

It felt like a validation, but more importantly, they started offering substantive suggestions. The small language models idea, the indirect knowledge propagation, the simulation-reality integration, these weren't just polite comments. These were researchers seeing potential and wanting to push the work forward.

You mentioned this might become a full paper. What's the publication strategy?

Research development is very publication-focused, and rightfully so. We're working on expanding this into a full paper.

The timing is interesting: next year, ICLR, the International Conference on Learning Representations, one of the top AI conferences, is being held in Rio de Janeiro. Having this major conference in Brazil feels significant, especially for work coming from Brazilian researchers and companies.

Let's zoom out. Where do you see this work fitting into the broader landscape of AI development? Everyone's talking about agents right now, but much of it feels speculative.

That's exactly right. There's a lot of hype around agents, but not enough rigorous experimentation on emergent behaviors in multi-agent networks.

What excites me is that we're not just building agents to complete tasks. We're exploring what happens when you create ecosystems of agents, when you give them memory, identity, social dynamics, economic incentives.

The unexpected behaviors, the barter between the Brazilian and Tibetan merchants, the cluster formation, the sentiment-driven interaction patterns, these aren't bugs. They're signals that we're touching something fundamental about how intelligence might organize itself at scale.

What are the practical implications? How does this connect to real business problems?

We're still in the experimental phase, but several applications are emerging.

More recently we've been developing a fully autonomous multi-agent network that runs a company by itself, basically a self-driven company. The agents in the group cooperate in a way to enable labor division, complex behaviour and even real-world market search. This system is already working and deployed into a vending machine in the office.

Think about training environments for negotiation strategies, product exchange by attributed value, or testing market dynamics before launching real products. Think about companion agents that learn organizational culture by interacting within a simulated version of your company.

Or consider this: what if you could create a digital twin of a marketplace, populate it with agents, and observe how different pricing strategies or product mixes perform before implementing them in reality? Our agent, JIM, has a personalized context for each client. It could be used as a proto digital twin that tests client products in a simulated marketplace, a kind of testing environment. Then, in the future being able to serve the clients as a digital merchant buying and selling their products.

The simulation becomes both a laboratory and a training ground.

There's something almost philosophical about this work, creating entities that exist just to exist, to interact, without predetermined purpose. Does that aspect interest you?

Absolutely. There's something profound about emergence, about complex behaviors arising from simple rules and interactions.

We're creating something closer to life than to traditional software. These agents aren't following decision trees or optimizing explicitly defined objectives. They're... existing. Adapting. Surprising us.

That's where the most interesting questions lie: What happens when intelligence becomes genuinely autonomous? What social structures emerge naturally? What economic behaviors arise without being programmed?

Before we finish, I want to ask about the Brazilian tech ecosystem. You're presenting this work internationally, but developing it in Brazil. How do you see the Brazilian AI research landscape?

Brazil has incredible talent, researchers, engineers, companies doing genuinely innovative work. But we're often underrepresented at major international conferences and in the global conversation.

That's changing. Having ICLR in Rio next year is a huge signal. Brazilian researchers are publishing at top venues, Brazilian companies are building sophisticated AI systems.

Work like this, developed in Brazil, presented at Stanford, engaging with the global research community, that's part of building bridges, showing that innovation isn't confined to the usual geographic centers.

It is also important to say that many projects in our R&D team are cutting-edge. Often, projects presented at conferences remind us of ideas that we have been applying for a while.

What's next for this project?

Immediate next steps: expanding the paper, incorporating the feedback from Stanford, running more extensive experiments with larger agent populations.

Medium term: exploring the integration points with real business infrastructure, understanding how these simulations can inform actual decision-making.

Longer term: I think we're just scratching the surface of what's possible with multi-agent ecosystems. The simulation-reality boundary, the emergence of unexpected social dynamics, the potential for these environments to become genuine training grounds for both AI and human understanding of complex systems. What kind of new tasks can agents perform when in populations? Are they able to cooperate to do a task that would be impossible with just a single agent? There's so much to explore.

Final question: and the Brazilian-Tibetan barter agents, are they still trading?

They are. Every simulation run, they find each other eventually. It's become this reliable pattern, they've built a relationship. Which, in a strange way, is exactly what we were hoping to see: persistent, meaningful connections emerging from repeated interactions.

Maybe that's the ultimate test of whether we've created something genuinely interesting: not whether agents can complete tasks, but whether they can build relationships.

Build the Future with Us: This multi-agent marketplace is just one of many cutting-edge projects at CloudWalk. Check our open positions and our Nimbus project.